New technology detects genetic diseases previously unable to be identified

World leading technology in identifying disease genes has arrived in Australia to facilitate new diagnostic genomic tests for patients with life affecting genetic conditions.

Funded by philanthropy through FSHD Global Research Foundation, Australia’s only funding body for the debilitating condition, Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD), the technology will provide answers for patients who have been previously mis-diagnosed or who have been unable to have their disease identified.

Executive Director of FSHD Global Research Foundation, Emma Weatherley said that it was critical Australians could access world class diagnostics.

“We want to lessen the burden for people trying to find the cause of their disease, but we also want to enable research, facilitate trials of new treatments, and ultimately find cures and to achieve all of these, gold standard technology was needed in Australia.

“We need to ensure our patient population is genetically diagnosed so we can bring clinical trials to Australia and offer them to people who have received accurate diagnoses. This new technology can detect genetic defects previously unable to be identified”, Ms Weatherley said.

FSHD is a highly complex disease that causes progressive muscle wasting, weakening and loss of skeletal muscle in adults and children, robbing them of the ability to walk, talk, smile, blink or even eat.

FSHD, is the second most common neuromuscular disease in Australia.

“This Bionano Sapphyr machine brings FSHD diagnostics into the modern age and advances us to clinical trial readiness in this country. This is a milestone moment for FSHD in Australia, providing world class diagnostic standards, more accurately, in half the time and at half the cost”, she said.

Since 2007 FSHD Global Research Foundation has funded over 55 medical research grants across 10 countries.

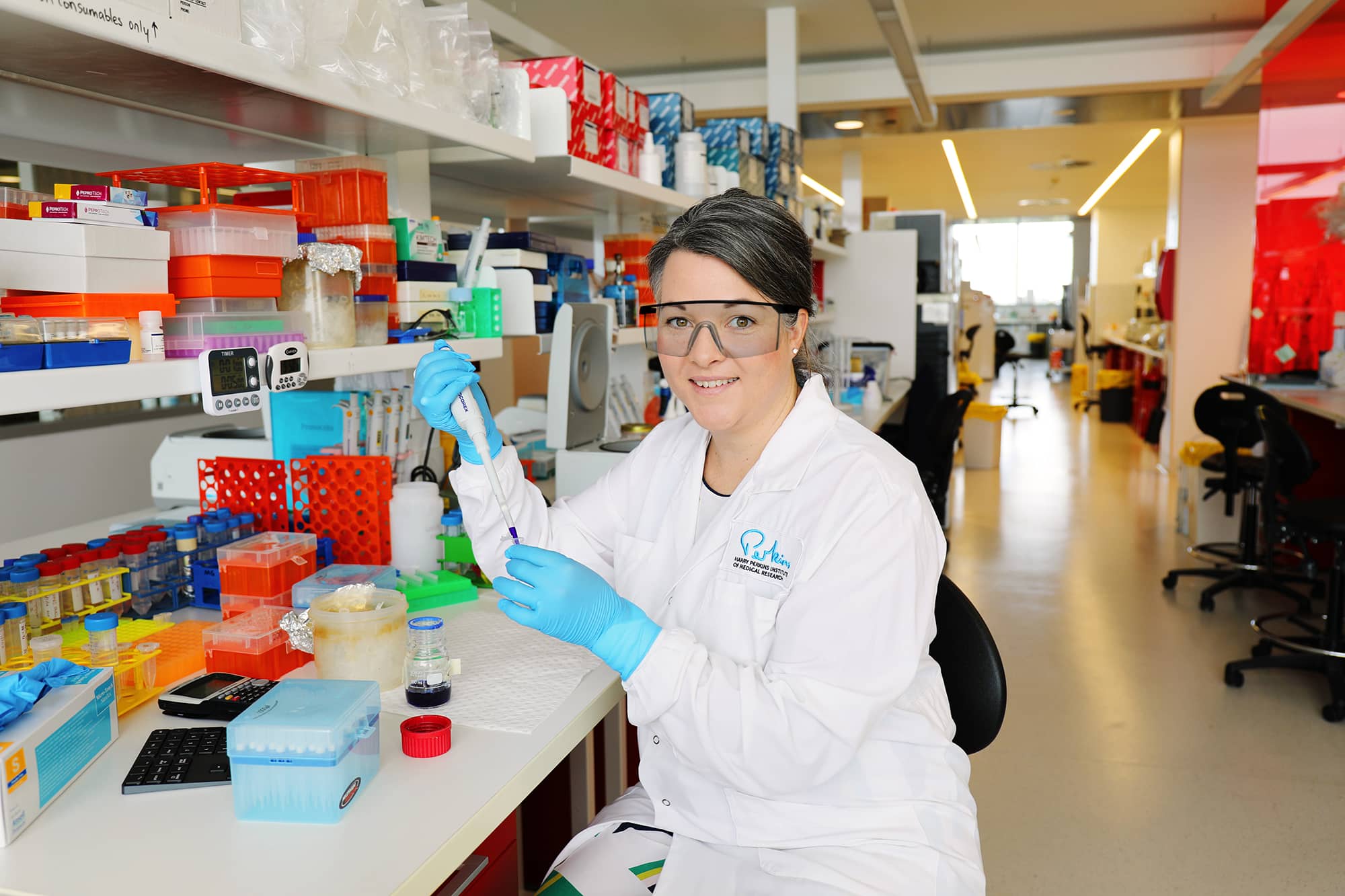

Head of the Rare Disease Genetics Group at Perth’s Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, Dr Gina Ravenscroft, said the Bionano will significantly advance Australia’s contribution to global research into muscle wellness, muscle technology and drug discovery to advance clinical trials for FSHD.

It will increase the number of diseases that can be diagnosed and enable cutting-edge genomic research.

“There are many debilitating genetic diseases. Some like FSHD greatly affect people’s daily lives, others can cause tragic symptoms such as recurrent miscarriages from premature ovarian insufficiency. Getting an accurate genetic diagnosis has important implications for patients and their families.

“They can know what’s ahead for them, know if they have a disease that will worsen over time, and make plans and choices.

“The opportunities the Bionano can provide will be life changing. In the past patients with serious life-affecting symptoms have been misdiagnosed”, she said.

Most diagnoses of genetic mutations use DNA sequencing but many neurodegenerative diseases, have very large mutations on the DNA that are too long to detect using traditional sequencing techniques.

“Instead of using DNA sequencing the Bionano uses a fluorescent marker to optically map ultra-long DNA fragments. This approach allows for the detection of types of genetic defects that can’t be easily picked up with normal DNA sequencing”, Dr Ravenscroft said.

Up until now in Australia FSHD has been diagnosed using a labour intensive, time consuming and expensive technique called Southern Blot testing.

A group of patients with neuromuscular disease symptoms has already provided blood samples to enable testing of the Bionano and a Melbourne geneticist has contacted the Perth team about a patient with chromosomal abnormalities and strong family history of reproductive issues.

The Bionano Sapphyr instrument is installed in Diagnostic Genomics, PathWest in a collaborative partnership between the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research, PathWest and FSHD Global Research Foundation, which contributed more than $500,000 to support the purchase and running costs.

Dr Ravenscroft said from a research perspective, accurate diagnoses of genetic diseases is critical to providing appropriate treatment.

“Knowing who has a genetic disease means that for organisations like the FSHD Global Research Foundation they can offer support and play a key role in helping the Australian community become ready for clinical trials of potential treatments as they become available,” Dr Ravenscroft said.

Patient story – a life of misdiagnosis

Rob Matthews, aged 73, was told in primary school he had Polio. He was regularly assessed by doctors at the Department of Health, Poliomyelitis Division in Melbourne.

“My symptoms were poor posture, weakness, pain and lack of stamina. I was fitted with a steel back brace to try and improve my posture. Later in high school my symptoms worsened. I remember doing the school external exams in the Exhibition Buildings and was given a separate area and additional time to enable me to complete the exams due to my pain.

Over the next three decades Rob found work in several roles, from the public service, to working as a ships officer, but each time pain, weakness and fatigue would force him to leave.

“During these years I played in weekend pop bands. There were years of success and touring, however the pain and weakness and fatigue continued until this too became impossible,” he said.

“My symptoms worsened, and I went to see a specialist for Post‐Polio Syndrome. I was diagnosed with Congenital Myopathy and that was that.” Rob continued to be treated as a Polio patient.

It was while searching the internet that Rob read the symptoms of a disease that sounded just like the ones he’d suffered throughout his life.

It was for the second most common neuromuscular disease in Australia, Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, known as FSHD.

That search led to an appointment at the Concord Repatriation General Hospital in NSW.

“I had one of the first DNA Southern Blot Tests in Australia and after 9 months my results came back positive for FSHD.

“It was always FSHD. There had been misdiagnosis after misdiagnosis. I never had Polio after all”.

Rob hopes that with much faster and more accurate diagnoses and research enabled by the Bionano machine, a cure for FSHD can be found, “especially to help the younger people make their way in life,” he said.